Wearable Technology: We Use It to Track Ourselves

But is it Tracking Us?

By Alex Knaub, Law Clerk

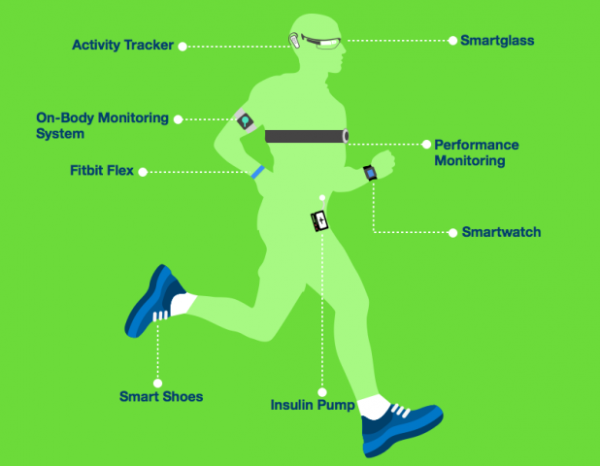

Wearable technology takes many forms: “Smartwatches” like Apple Watch, activity trackers such as Fitbit, GoPro wearable cameras, and location trackers like Tile are all the rage. We live in the future where a small device that you wear on your wrist tracks your daily activity, sleep patterns, heart rate, breathing patterns, steps taken, GPS location, calories burned, body composition, glucose levels, and more.

Ask yourself these questions:

Should we be concerned that all of our daily information is being tracked and collected? Who has access to this information? Who owns the information? What can they do with the information?

Lawyers are asking these questions, and frankly, the answers are not readily apparent, nor are they comforting. No one knows the extent to which this technology will be adopted and used in litigation

A fictional story illustrates this concern:

Stephanie is a single mother with two small children, ages 3 and 5. Her children and her two jobs keep her busy for most of each day. About two years ago, Stephanie bought a wearable device that tracks her activity levels and sleep patterns. She bought it shortly after her youngest daughter’s first birthday with the idea of getting back in shape. She is busy person and likes the ease of use of her device. She has been dedicated to using her device every day since she bought it.

Six months ago, Stephanie was involved in an accident in a grocery store. She was walking down an aisle when the freezers exploded, and she ran for cover. While so doing, she slipped on a puddle of banana pudding. She fell hard. Stephanie was rushed to the hospital. She filed a lawsuit against the store.

At this point in the story, stop for a moment and evaluate how Stephanie’s wearable device might be used in the litigation. First, can the wearable device information be used? The short answer is “yes.” The more probative question is how will the information be used?

Stephanie could use the information herself to bolster her claims of injury, showing her activity levels pre- and post-accident. A law firm in Calgary has started using this exact type of information to support its clients’ injury claims, arguing that using the wearable device data to track the injured person’s activities on a daily basis can show the effects of an injury to a jury more effectively than simply telling them. A jury can see the difference between 10,000 steps per day pre-accident and 1,000 steps per day post-accident.

The advantage here is that sometimes seemingly small accidents can indeed lead to catastrophic injury. The type of injury that requires lifetime care can and does happen from a slip-and-fall injury. When serious injuries occur, having data is extremely helpful to overcome the natural skepticism concerning a three-million dollar slip-and-fall.

Luckily for Stephanie, her lawyer knows all about wearable devices and their utility in the courtroom. Unfortunately, her lawyer lacks scruples. He tells her what her activities levels should be post-accident, so the comparison of activity pre-accident and post-accident is dramatic.

Now we know, this “reliable” data can be easily manipulated.

If this “reliable” data can be easily manipulated, does it have any value? Well, all data can be manipulated, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t have value.

Fortunately, Stephanie fully recovers from her fall, returns to work as a truck driver where she hauls oranges up and down the California coast. She manages to make it home every night. To accomplish this, Stephanie never sleeps. She lies to her employer and says she is always well rested before driving.

Stephanie was involved in a terrible trucking accident when she fell asleep behind the wheel. Her attorney learns that Stephanie wore her wearable device at the time of the accident. Stephanie’s latest model of wearable technology tracks her levels of fatigue and tells her when to sleep. Panic sets in, as the attorney looks through her wearable data. The attorney’s hopes of winning this case are dashed because the device data shows Stephanie never sleeps and always silences her sleep alarm. He hopes the injured party’s attorney will not think to subpoena the records from Stephanie’s device; he wonders whether the employer should have monitored the devices of his drivers given the technology is available.

Wearables have not become the standard, yet. This is fortunate, as most of us don’t think how this data can and will be used. Perhaps this data will reduce frivolous lawsuits by disproving exaggerated damages. Perhaps the data will help prove up damages in seemingly innocuous cases. Perhaps employers will use the technology to track their employees using wearables.

As these uses for our data develop and evolve, wearable technology grows both in popularity and application. Many of us, and more every day, wear a device on our wrist that tracks our every movement. Most of us, almost all of us, have a device in our pocket or our purse that logs all of our communications.

Are we delusional when we say we still have a reasonable expectation of privacy in the land of technology?