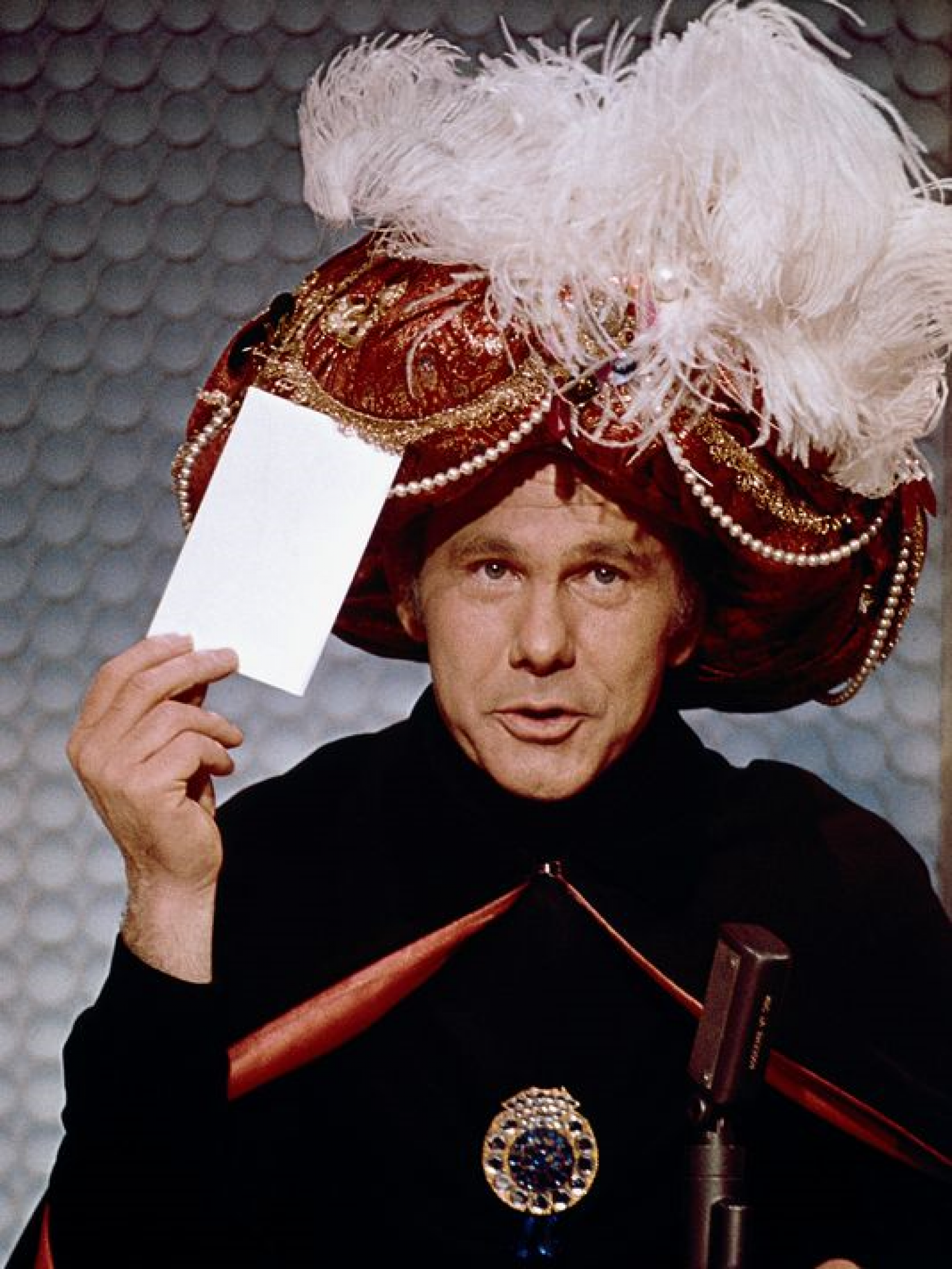

Carmack The Magnificent: Understanding the Application and Preemptive Ambit of the Carmack Amendment to the Interstate Commerce Act

For more than a century, the Carmack Amendment to the Interstate Commerce Act (49 USC 14706) (“Carmack”) has governed the liability of motor carriers operating in interstate commerce. While the Congressional purpose in enacting Carmack was to a uniform liability scheme which “creates uniformity out of disparity”, most practitioners (and even some judges) have had little exposure to Carmack and, thus, are unaware of its vast preemptive ambit. It is hoped that this article will provide practitioners, and jurists, with the nuts and bolts of substance, and procedure, applicable to claims arising under Carmack

Federal law and procedure is applicable in actions when a shipper seeks recovery against a motor common carrier for damages sustained to cargo incident to an interstate move. The interstate transport of cargo by a motor common carrier triggers the application of the Carmack amendment to the Interstate Commerce Act. 49 U.S.C. Section 14706 et seq.

The Carmack amendment addresses the subject of a motor carrier’s liability for goods lost or damaged during the course of an interstate move. Congress enacted the Carmack amendment to provide uniformity and predictability to a common carrier’s liability for an interstate property loss.

From a common carrier’s perspective, the most important aspect of the Carmack amendment is that it limits a shipper’s recovery to the actual loss or injury caused by any of the carriers involved in the shipment. The actual-loss language of the statute is the source of the statute’s vast preemptive effect. In fact, shortly after its enactment in 1906, the Supreme Court stated that the subject of a carrier’s liability is “covered so completely [by the Carmack Amendment] that there can be no rational doubt but that Congress intended to take possession of the subject, and supersede all state regulation with reference to it.” Adams Express Co. v. Crominger, 226 U.S. 491 (1913).

All federal circuit courts addressing the issue have held that the Carmack amendment preempts a shipper’s state-law claims seeking recovery for damages sustained during the course of an interstate shipment. Lloyds of London v. North American Van Lines, Inc., 890 F.2d 112 (10th Cir. 1989). In addition, the actual-loss language of Carmack has been held to preempt a shipper’s state-law claims involving conduct occurring before and after the actual interstate transport of the shipper’s property. Hall v. North American Van Lines, Inc., 476 F.3d 683 (9th Cir. 2007).

Various circuits have held that the Carmack amendment preempts state-law claims for negligence, fraud, gross negligence and tortuous interference with economic advantage premised upon pre-shipment conduct. Cleveland v. Beltman North American Co., 30 F.3d 373 (2d Cir. 1994). Similarly, a majority of circuit courts have held that a request for tort damages premised upon a carrier’s post-transport conduct to handling a shipper’s damage claim does not escape the vast preemptive effect of the Carmack amendment. Rini v. United Van Lines, Inc., 104 F.3d 502 (1st Cir. 1997).

Carmack also provides a carrier with two other mechanisms to potentially eliminate, or reduce, its liability for damages. The first is 49 U.S.C. Section 14706(e) which authorizes a carrier to preclude a shipper’s recovery where either the shipper fails to provide a written claim within nine months from the date the damaged property is delivered or, in the case of a common carrier’s failure to deliver, within nine months after a reasonable time for delivery has elapsed; and where a shipper fails to initiate a civil action against the carrier within two years after written notice is given that the carrier has disallowed any portion of the claim.

Like most other claim-filing statutes, the purpose of Section 14706(e) is to avoid stale claims and to provide the carrier with an opportunity to investigate a claim while witnesses and the damaged property are still available. Furthermore, a shipper’s claim that he or she did not have knowledge of the limitations provision is of no legal import, as the shipper is chargeable with knowledge of the law. See Aero Trucking, Inc. v. Regal Tube Co., 594, F.2d 619 (7th Cir. 1979).

The second mechanism is the “declared-value” limitation. Prior to the disbanding of the Interstate Commerce Commission (effective Jan. 1, 1996), the statutory provision entitling a carrier to limit its liability to a declared value was found at 49 U.S.C. Section 10730, which provided that “the Interstate Commerce Commission may require or authorize a carrier… to establish rates for transportation of property under which the liability of the carrier for that property is limited to a value established by written declaration of the shipper, or by a written agreement, when that value would be reasonable under the circumstances surrounding the transportation.” The post-1996 version of this statute is found at 49 U.S.C. Section 14706(f). This statute remains a viable defense for motor common carriers.

Before a carrier’s attempt to limit its liability will be effective, the carrier must maintain a tariff in compliance with the requirements of the Interstate Commerce Commission (now the Surface Transportation Board): give the shipper a reasonable opportunity to choose between two or more levels of liability; obtain the shipper’s agreement as to his or her choice of carrier liability; and issue a bill of lading reflecting such agreement prior to moving the shipment. The absence of any one of these factors will deprive the carrier of this useful defense. See Hughes v. North American Van Lines, Inc., 970 F.2d 609 (9th Cir. 1992).

Typically, an aggrieved shipper files an action in state court, asserting various state-law causes of action in order to expand the shipper’s potential recovery. Often, a shipper will supplement its breach-of-contract action with tort theories, such as conversion, negligent infliction of emotional distress and breach of the implied covenant of good faith and fair dealing. The latter are usually asserted where the claims-handling process has taken longer than the shipper believes was warranted.

As a general rule, federal courts are more apt than state courts to apply the provisions of the Carmack amendment to limit a shipper’s recovery. Thus, the first step upon receipt of a cargo claim is to determine whether the matter is removable to federal court. There are three primary considerations: Does the complaint seek recovery for goods damaged during the course of interstate transport? Does the dollar amount of property damage sought meet the $10,000 jurisdictional minimum of 28 U.S.C. Section 1445(b)? Is removal time-barred?

The first question is usually straightforward. More often than not, the complaint alleges, for example, that “shippers’ goods were damaged while being transported from New York, New York, to Los Angeles, California.” This allegation alone, assuming the existence of the other considerations, triggers the application of the Carmack amendment.

However, even if the goods were damaged while still in the state of the origin, this does not defeat removal jurisdiction. In fact, all that is required is that the goods be damaged incident to their interstate transport. New York N.H.H.R.Co. v. Nothnagel, 346 U.S. 128 (1952). Thus, for example, federal jurisdiction would still lie over a shipment originating in New York state and destined for North Carolina, where the carrier’s vehicle overturned in New York prior to even crossing the New York state line. This is because the shipper’s intent was to ship the goods in interstate commerce. Likewise, in Hall, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeal held Carmack to be applicable even though no physical transportation of the subject goods had occurred.

The second consideration is readily addressed in 28 U.S.C. Section 1445(b), which provides that a cargo claim of less than $10,000 is not removable. However, the fact that a shipper requests damages of more than $10,000 is not determinative. For example, the 9th Circuit has held that he property-damage component of the claim must alone surpass the $10,000 minimum to render a claim removable. A carrier cannot bootstrap federal jurisdiction over the other components of a claim (i.e., bad faith, emotional distress, fraud) by asserting that the total amount sought is in excess of $10,000. See Hunter v. United Van Lines, 746 F.2d 635 (9th Cir. 1984).

The last preliminary consideration is addressed by 28 U.S.C. Section 1446(b), which provides that an action must be removed within 30 days after service of the first pleading that sets forth a removable claim. This procedural consideration was recently addressed in Steiner v. Horizon Moving Systems Inc., 568 F.Supp.2d 1084, (C.D.Cal. Jul 25, 2008), which held that a Notice of Removal filed well into the litigation is appropriate where discovery reveals the federal question basis of same. Thus, a practitioner must remain vigilant as to her/his ability to remove a matter even after the initial pleading stage.

Upon removing the action to federal court, a carrier should attempt to “clean up” the shipper’s complaint in order to eliminate all of the state-law claims contained therein. This cleansing can be accomplished by filing a motion to dismiss for failure to state a claim pursuant to Federal Rule of Civil Procedure Section 12(b)(6).

At this stage, counsel for the shipper will usually attempt to challenge the extent of the Carmack amendment’s preemptive effect. However, the following authorities can be cited to demonstrate the breadth of the Carmack amendment’s preemptive effect over claims involving pre-shipment conduct (Pietro Culotta Grapes v. Southern Pacific Transport, 917 F.Supp. 713 (E.D. Cal. 1996)); post-shipment conduct (Cleveland v. Beltman North American Co., 30 F.3d 373 (2d Cir. 1994)); negligence (Hughes v. North American Van Lines, Inc., 970 F.2d 609 (9th Cir. 1992)); negligent misrepresentation (Hughes v. United Van Lines, Inc. 829 F.2d 1407 (7th Cir. 1987)); conversion (Schultz v. Mayflower Transit, 848 F.Supp. 1497 (D. Idaho 1993); breach of the implied covenant of good faith (Pietro Culotta and Cleveland); fraud (Moffit v. Bekins Van Lines Co., 6 F.3d 305 (5th Cir. 1993)); and consumer-protection statutes (Margetson v. United Van Lines, Inc. 785 F.Supp. 917 (D. New Mexico 1991).

Once a claim under Carmack is properly venued, and appropriately plead, a practitioner should review the many defenses — statutory and/or common law — that may exist to defeat or reduce a shipper’s claim. Hopefully, this article will serve as a general framework regarding how, where, and when to utilize the preemptive ambit of Carmack to your client’s advantage.